Four Scrapers

I wrote a web scraper in four different languages.

A rebuke of “hello world” in Node, Go, Python, and Rust.

hello world in Rust

hello world in Rust

We’ve all written this at one point or another, and honestly this patronizing exercise needs to stop. I get it, you learn how to set up a project, whatever tooling is necessary, and maybe some basic syntax. However it’s far from an ‘introduction’.

With a front end framework one might make a ‘todo’ app. This gives a rounded view of state, user input, crud interactions, and layout. But what if I don’t care about front end interactions?

Some questions I have asked myself in each of these scenarios: How do I import methods I may need to use? How do I interact with the filesystem? How can I get a resource remotely (http request)? Once I have that resource how can I interact with it? A project that covers all of these concepts would be a simple web scraper.

caveat — web scraping is a point of contention, some say it’s unethical, bordering on illegal. While I don’t agree with that opinion I would advocate that you exercise caution if you plan on making and using a tool to collect data from web sources. Done incorrectly this can be destructive, be careful.

I have some experience with web scraping. I find it enjoyable to tinker with in my spare time, and I have worked professionally on projects that involve some fairly comprehensive setups. For this experiment, I want to use standard package methods. This way we get the benefit of gaining some familiarity with the language, rather than learning the API of a particular package.

Requirements —

make an http request for a page

store that page locally on the filesystem (making sure that we do not overwrite a previous scrape)

read that file from the disk

use native methods to find a search term

Attaining these four goals involves a much deeper understanding of each language than printing some Tiger Woods quote (😝, I‘m aware it’s from C). We will learn how each language handles asynchronous behavior, how it reads and writes files, and deals with primitives. Not to mention we will also be printing something meaningful to the console.

- NodeJS -

I work daily in JavaScript, this will set the bar for what I want to replicate in other languages. Keeping as much as possible native and simple. I came up with this:

const { get } = require('https')

const { readFileSync, writeFileSync } = require('fs')

const checkPageForText = (page, text) => {

// Make the http request for the resource

get(page, resp => {

let data = ''

// Build the 'data' string as chunks come in

resp.on('data', chunk => (data += chunk))

// Response has ended, we have completely built our data

resp.on('end', () => {

// Create a unique token for filename

const token = new Date().valueOf()

// Write data as a file to disk

writeFileSync(`scrape-${token}.html`, data)

// Read the file and check if the search term is present

if (readFileSync(`scrape-${token}.html`, 'utf8').includes(text)) {

// Return a message to the user that the search term was found

console.log(`${text} exists on ${page}`)

} else {

// Return a message to the user that the search term was not found

console.log(`${text} not found on ${page}`)

}

})

})

}

checkPageForText('URL', 'searchTerm')We have imported three native methods, get which will fetch our page, and then readFileSync and writeFileSync functions that are blocking (they behave synchronously). When we call checkPageForText it takes a URL and a term. It first makes an http request for the resource (url), when the data stream comes in chunks it builds a data string out of those chunks.

Once the stream ends, it takes that string and writes it synchronously to the disk. Here is where a timestamp is important so that we aren’t constantly overwriting scraped data. It’s possible this way to reference historical data if the page contains a search term we can do further parsing of that file. Using a simple if check we read the file which we just wrote, then use the native javascript includes String method to find our term.

JavaScript is asynchronous, and we use callbacks in this case to handle a response returning from a request and access data when it is completely transferred. Callbacks can get messy if over-used and can create a ‘pyramid of doom’.

Another solution would involve promises, and could even involve async and await keywords. For this application using callbacks works fine and is fairly easy to follow. Some describe JavaScript as ‘expressive’, in this case there are a number of approaches that would achieve the same outcome.

Overall we have a basic scrape of a page and can find a search string and report that back to the user. This could be much more robust, however making a comparison between languages becomes harder, and less meaningful the more complex the application.

- Go-lang -

Here we follow the same steps as in the Node implementation. scrape takes u for a URL, and t for term or search term. The convention for single character variables in Go is exactly contrary to how I learned to write readable code. It is, however, their conventions so I must abide.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io/ioutil"

"net/http"

"strconv"

"strings"

"time"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println(scrape("URL", "SearchTerm"))

}

func scrape(u string, t string) (string, error) {

// Make the http request for the resource

resp, err := http.Get(u)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

// Close the connection when the response is complete

defer resp.Body.Close()

// Read the response body to a variable

body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

// Create a unique token for filename

ts := strconv.FormatInt(time.Now().UTC().UnixNano(), 10)

// Generate a string for the filename

filename := fmt.Sprintf("scrape%v.html", ts)

// Write body as a file to disk

ioutil.WriteFile(filename, body, 0644)

// Read the file to a variable

dat, err := ioutil.ReadFile(filename)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

// Check if the search term is present

if strings.Contains(string(dat), t) {

// Return a message to the user that the search term was found

return fmt.Sprintf("Found %[1]s in %[2]s", t, u), nil

}

// Return a message to the user that the search term was not found

return fmt.Sprintf("%[1]s was not found in %[2]s", t, u), nil

}Error checking is a known pain point in working with Go. You can see the successive error checking with each possible fail point. On one hand this is repetitive, however it does make it easier to debug.

A huge difference in moving from a dynamic language like JavaScript to Go is that we have to define our types and when appropriate cast our byte slice into a string (line 49). This has clear advantages in type safety, also in thinking through exactly what your function needs in order to return the correct type.

After some collaboration with someone more familiar with Go, I was able to streamline some ugly string concatenation (using Sprintf instead of +) and better understand the naming conventions in Go. When passing variables to a function use one or two letters, otherwise something like filename or body is fine. Go stands out in this list as an accessible strongly typed language.

- Python -

Straightforward is how I would describe writing Python. It is no wonder this is a first language choice for many new programmers. Python’s user base is massive, and support is ubiquitous.

from urllib2 import urlopen

import time

def scrape(url, term) :

## Make the http request for the resource

response = urlopen(url)

## Read the response body to a variable

html = response.read()

## Create a unique token for filename

ts = time.time()

## Generate a string for the filename

filename = "scrape" + str(ts) + ".html"

## Write html as a file to disk

f = open(filename, "w")

f.write(html)

## Open the file

s = open(filename, "r")

## Read the file and check if the search term is present

if term in s.read():

## Return a message to the user that the search term was found

return "Found " + term + " in " + url

## Return a message to the user that the search term was not found

return term + " was not found in " + url

print scrape('URL', 'SearchTerm')Here we make the same scrape program with the same url and term parameters. The code is so simple and easy to follow along I almost don’t think it requires explanation.

One issue I will point out here is that Python, rather than having clear syntax using curly braces to visually show a block, relies on whitespace. I don’t prefer this, though I do see the elegance.

I understand that this quality of Python is what makes it accessible and why so many people use it. I love the ability here to simply write if term in s.read() without having to invoke a method to search a string. Python strikes me as utilitarian, and to that point an extremely powerful general purpose language.

- Rust -

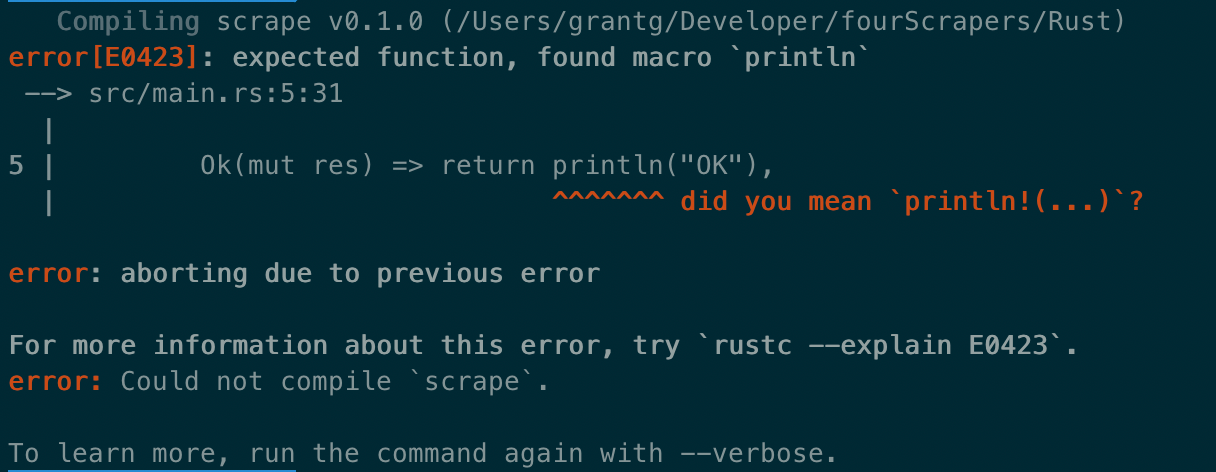

Right off the bat Rust is a totally different animal to the previous languages in this article. One amazing thing about Rust is that it’s compiler errors are actually human readable and very helpful.

I think they’ve really gone above and beyond here trying to take the pain out of something that could easily have become less important while developing the tooling for Rust. After coding for significantly more time than the other languages in this article, this is the Rust scraper:

extern crate reqwest;

use std::time::SystemTime;

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::prelude::*;

fn write_file(filename: &str, data: &str) {

let bytes = data.as_bytes();

let mut file = File::create(filename).expect("Error creating file");

file.write_all(bytes).expect("Error writing file");

}

fn read_file(filename: &str) -> String {

let mut file = File::open(filename).expect("Error opening file");

let mut contents = String::new();

file.read_to_string(&mut contents);

return contents;

}

fn gen_timestamp() -> String {

match SystemTime::now().duration_since(SystemTime::UNIX_EPOCH) {

Ok(n) => n.as_secs().to_string(),

Err(_) => panic!("SystemTime before UNIX EPOCH!"),

}

}

fn scrape(url: &str, term: &str) -> String {

// Make the http request for the resource

// and assign the text response to a variable

let response_text = reqwest::get(url)

.expect("Unable to find url")

.text()

.expect("Unable to read response");

// Create a unique token for filename

let timestamp = gen_timestamp();

let filename = ["scape", ×tamp, ".html"].join("");

// Write the response text to disk

write_file(&filename, &response_text);

// Read the file to a variable

let scrape_data = read_file(&filename);

// Check if the search term is present

if scrape_data.contains(term) {

// Return a message to the user that the search term was found

return ["Found", term, "in", url].join(" ");

}

// Return a message to the user that the search term was not found

return [term, "was not found in", url].join(" ");

}

fn main() {

println!("{}", scrape("URL", "SEARCH_TERM"));

}I had a hard time finding a straightforward way to make an http request with the standard library and wound up using an external crate (package/library) called reqwest.

A concept that was required to write this program in Rust was that of ‘borrowing’. Borrowed variables are their own type in Rust, they’re a reference back to the place in memory where the variable is stored (sounds like a pointer to me, I don’t understand this enough to differentiate). Memory management is something many programmers using higher level languages don’t deal with as explicitly.

I mentioned earlier that one pain point in Go was error checking. Rust does not have this problem, in fact the programmer in Rust is given options in how and when to handle errors depending on how information is being accessed or generated. You can see this in the difference between get_timestamp and read_file.

When reading a file we have used the .expect() syntax to handle an exception, while the timestamp generation uses a Result enum to handle the error. I like options, and surprisingly despite my struggles with it I really like Rust. I wouldn’t be comfortable reaching for it to quickly prototype an idea, but my interest has grown.

Wrapping up

Each of these languages has a different purpose, they solve different problems. A couple of these languages (Python and JavaScript) seem to have solutions for every problem. But as such they lack efficiencies and safety that Go and Rust excel in.

Some with more experience in these languages are sure to find better/different ways to achieve the simple scraper and I am looking forward to seeing how some might implement it. Or if you have a different program that you like to write when getting acquainted with a new language, please share it.

As far as “hello world” is concerned, a simple scraper is much more involved. I want to demonstrate that an introduction to a programming language can be so much more in depth and show off its features, syntax, strengths, and weaknesses. By no means is this a solution to a real problem, just something I wanted to explore. I hope you find this useful and decide to contribute your own scraper or something better.